The sun usually shone in my childhood memories, except that the Met. Office records say it did not. Similarly, one step on from the myth of the ‘noble savage’, we may imagine that prior to 1945 or 1900 or 1800 there was a period when sturdy peasants valued their trees and woods as part of the local economy, living in harmony with their environment. In the 1980’s ancient woods were often quoted as examples of long-term sustainable management. At the individual site level that might be true, if we ignore nutrient depletion by tree harvesting and litter collection, restriction of regeneration by high levels of grazing, direct/indirect selection for some species (both plant and animal) and extirpation of others, soil disruption in the creation of banks, ditches, charcoal hearths, sawpits, even occasional arable catch-crops.

(a) One of many charcoal hearths in this oakwood (ok this is in Wales); (b) an extirpated species

At the national level there is a different picture. Oliver Rackham’s interpretation of the Domesday Book woodland records led him to conclude that woodland cover was only about 15% of the land surface at the end of the 11th Century (Rackham, 2003). That figure, if also applicable to the five northern counties not covered by Domesday, suggests a total area of about 1.95 million hectares wooded ground in England. Any woodland that survived from then to the present would now be classed as ‘ancient’, because it would clearly pre-date 1600 CE.

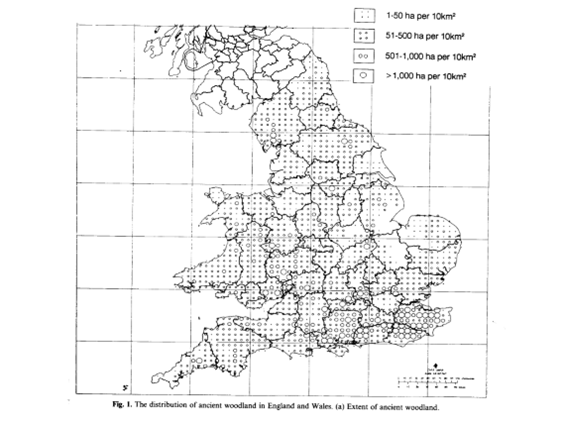

(a) Map of Domesday woodland from Rackham (2003); (b) Distribution of ancient woodland in the 20th century (Spencer and Kirby, 1992).

The first ancient woodland inventory estimated that there was about 0.37 million hectares of ancient woodland in England (2.8% land surface) in the 1930s, some of which is known to have developed in the Medieval period, post-Domesday (Spencer and Kirby, 1992). The current revision of the inventory has identified other areas that should be classed as ancient: a generous estimate might be a 40% under-recording (giving a total of c.0.52 million ha), although that would imply that about three-quarters of the woodland present in 1905 (c.0.68 million hectares) was ancient. Very roughly then, it looks like 1.4 million hectares of potential ancient woodland in England were cleared over the 800 years from 1100-1900 CE. This is about 175,000 ha per century, or an average rate of 1750 ha per year. For comparison Spencer and Kirby estimated ancient woodland clearance between 1935 and 1985 to be about 26,500 ha, an annual rate of 530 ha a year.

(a) size distribution for parcels of woodland cleared between 1935 and 1985 (from Spencer and Kirby, 1992); (b) an extensive post-WWII clearance at Ongar Park Wood, Essex.

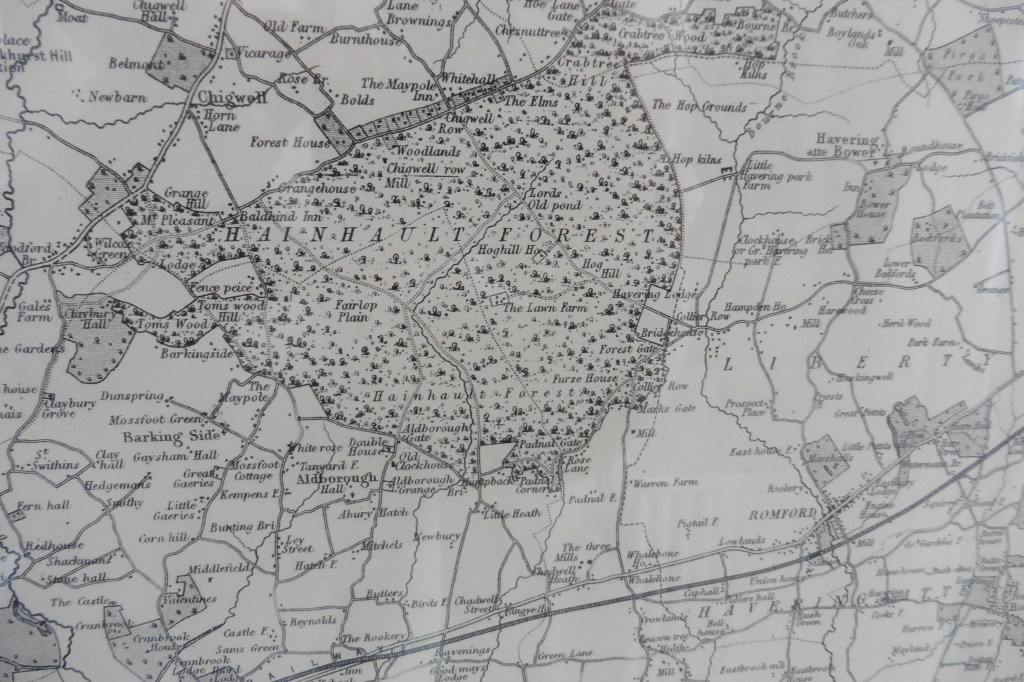

An annual clearance of 1750 ha would equate to about 40 ha per county, often just nibbling away at the edges of ancient woods: most of the losses between 1935 and 1985 were similarly in parcels of between 2 and 5 ha (losses of woods under 2 ha were not recorded). Occasionally much larger blocks might be lost such as happened with Hainault Forest in the mid-19th century. The rate would almost certainly have been irregular – periods of high woodland clearance, for example being driven by rising population, or when foreign wars put a premium on home- grown food production, interspersed by periods of little change and perhaps even woodland recovery, such as after the Black Death. Wood production was important locally, but from the 14th century onward timber and wood were imported to fill the growing gap between home production and consumption.

(a) Hainault Forest c.1850 and in 2017.

If the above calculations are correct it suggests the 20th C rate of ancient woodland loss was not atypical in absolute terms, although it was clearly a much higher percentage of the surviving woodland resource than in previous centuries. In addition, a new element was the large areas of semi-natural broadleaved stands converted to coniferous plantations, although the extent to which this happened also in the 19th century has probably been underestimated.

Communities of the past, like those of the present, were driven by the need to survive, to improve conditions for themselves and their children. And the message of the last 1000 years is that woods standing in the way of achieving this were cleared. Ancient woods are still under threat, but there is more appreciation and protection for them than in the past.

RACKHAM, O. 2003. Ancient woodland: its history, vegetation and uses in England (revised edition), Dalbeattie, Scotland, Castlepoint Press.

SPENCER, J. W. & KIRBY, K. J. 1992. An inventory of ancient woodland for England and Wales Biological Conservation, 62, 77-93.