A long march, a long march, and twenty years behind, but the girl I met at Clusium comes easy to my mind.

The above comes from an imagined Legionary marching song, used in a 1950s’ radio adaptation of The Eagle of the Ninth: I was about five but listened with my older brother. Fragments of the verses and the tune have been running through my head in the last few days. My brother later studied classics and one summer walked Hadrian’s Wall with his school-mates. A recent tree conference in Carlisle provided an opportunity to follow in his footsteps. I did not do the whole length of the Wall but the 25 mile section in the middle included many of the highlights. Nearly two thousand years since it was built it is still an impressive and awe-inspiring feat of engineering: what will HS2 look like after that length of time?

Part of the wall and remains of a bath-house

Only the stones remain, but substantial amounts of wood must have been involved in the scaffolding for the buildings and their roofs; in the lesser buildings of the settlements that grew up behind the Wall to service the garrisons; and for firewood. Where were the woods that supplied the Wall, what did they look like? There is not much ancient woodland left either side of the boundary except along the river valleys. How much did Romans also exploit the local coal?

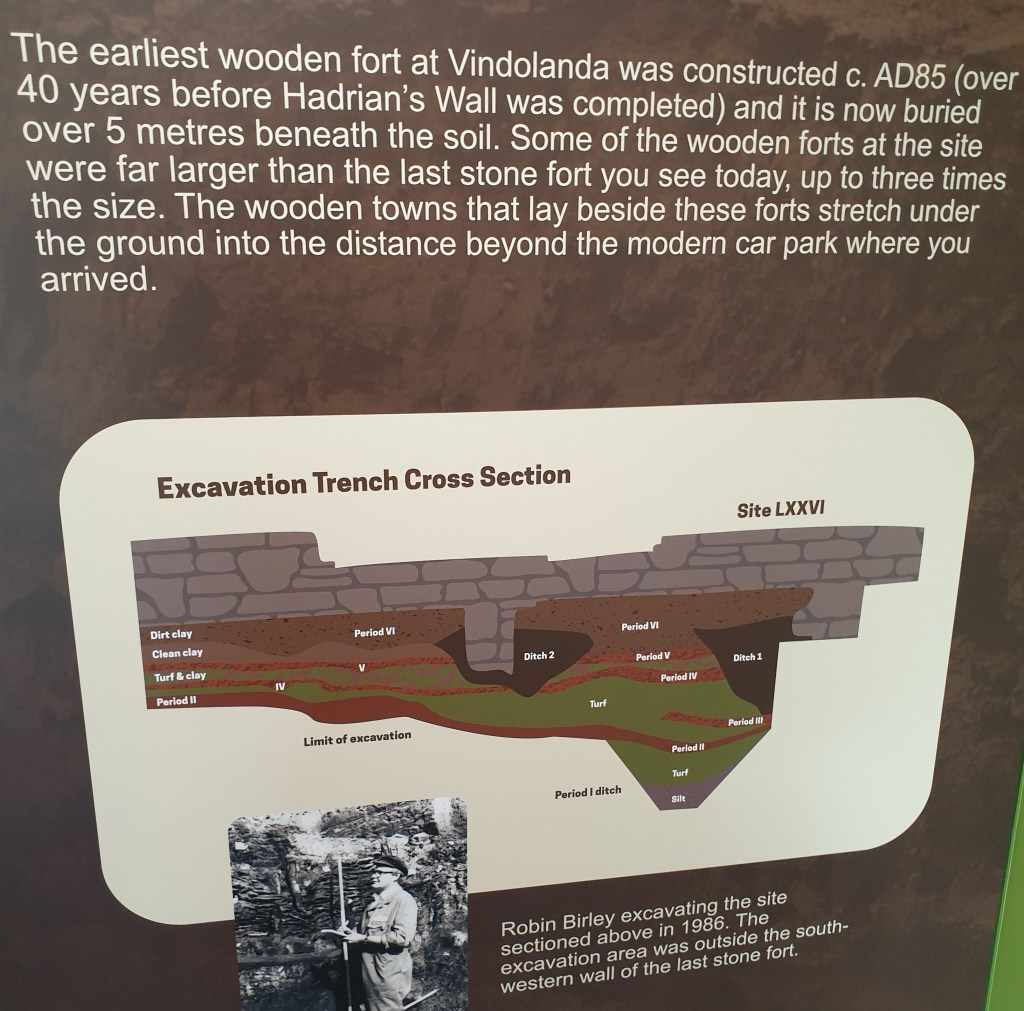

The fantastic site at Vindolanda provides direct evidence of the Romans’ use of wood. The remains of the stone fort that are visible are from the 3rd century CE, but there had been a series of wooden forts on the site before then. As each was knocked down and rebuilt with a new clay surface laid down over the rubble. This created anoxic conditions below that allowed the preservation of a wealth of organic and other matter. This includes wooden tools and bits of wooden structures including the lower portion of a large post cut from a 300 yr-old oak tree, which had started to grow c.270 BCE. At the other end of the scale are the wooden tablets on which are written letters dealing with the everyday live of the fort and settlement.

Sign board and view of Vindolanda stone fort

Oak is the most frequent species found (40% of samples). Its bark may also have provided the tannins needed to produce all the leather shoes that have been found here. Other trees identified include larch and silver fir that may have come in as worked timbers from abroad that were then re-used. Was the pine also imported or was it from remnants of mixed pine forests that once covered parts of the Border Uplands?

Remains of large post made from 300 yr-old oak; were there still local pine for the legionaries to use?

On my second day I came to Sycamore Gap. One of the papers at the conference had been about attitudes to sycamore amongst the conservation sector (often very negative), and other presentations touched on what makes an ‘important’ tree. Age and wildlife value featured strongly; but the felled sycamore was not particularly old (120-150 yrs) nor of any special biodiversity concern. It was not a native tree species, but there is no doubting that it was very important to many people. I wish the sprouts from its stump well. With many of the local ash showing serious ash dieback, the area needs its sycamores.

Regrowth on the Sycamore Gap tree stump; ash nearby showing bad dieback.

Beech was common in some of the shelterbelts and other small plantations. Even if we had not given it this helping hand, it would probably have spread north by now and further spread with climate change seems likely. Looking north from the Wall I could see some of the big plantations of spruce that stretch across the Borders, immigrants from North-West America. We need them to meet our timber and carbon targets, just as the Wall depended on legions and auxillaries from throughout its empire.

Beech providing glorious autumn colour and Sitka providing much needed wood.

So will the Old Man be signing on for a 20 yr stint with the Eagles – I don’t think so, two days marching left my legs stiff and aching – that was enough.