Production foresters developed a concept termed the ‘normal forest’ which is simply one in which all age classes for a give rotation length are equally represented by area. So, in theory you could harvest the same extent of woodland each year in perpetuity, as long as it is immediately restocked: i.e if the rotation is 100 years and you have 100 ha of woodland, then 1 ha a year can be felled and restocked. It is the same concept used in deciding how much coppice can be cut sustainably: if you have a 10 ha wood, and want to run a ten- year coppice rotation , 1 ha can be cut each year; if you have a 20 ha wood, 2 ha a year can be cut annually.

This coppice block is about a hectare, so as long as the wood is at least 20 ha, a 20-yr coppice cycle could be maintained indefinitely.

It is more complicated in practice. Areas that are set aside from production have to be taken out of the equation first. Sites are not uniform, so rather than equal areas cut each, year the cut ought to be based on areas of equal production. If harvesting is only periodic rather than annual, then several years’ allocation can be harvested at one time as long as there is an equivalent multi-year gap before the next harvest.

There are about 40 ha of oak on this site, so if grown on a 120 yr rotation, a 2 ha block, such as this, could be felled and restocked every 6 yrs.

The concept can also be applied to more natural situations, if there is a big enough population of trees or extent of woodland that they would maintain themselves indefinitely. For a 6,000 ha forest, where trees have roughly a 300 year life cycle, on average we might expect 20 ha of each year class across the forest, or more realistically, about 400 ha in each 20-year age band, allowing for year-to-year variations in recruitment and mortality.

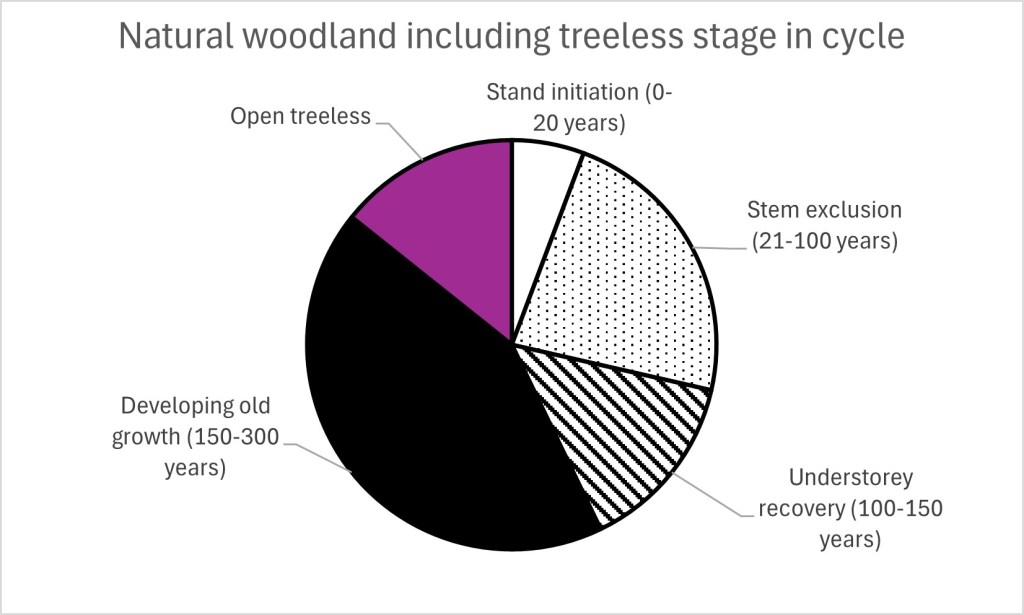

We can combine this with another idea, that of stand growth stages; the idea that any stand of trees (from a small group to a 100 ha even-aged planting) if left alone might be expected to go through four broad stages: the semi-open stand initiation stage; the stem exclusion stage when the trees close canopy and capture the site’s resources; understorey recovery as the trees grow and some gaps start to form; and if left long enough, the developing old growth stage as branches die back, hollows start to form in the trunks and decaying wood accumulates. These stages last different lengths of time, but if the system is sustaining itself, then applying the ‘normal forest’ concept the rough breakdown of the landscape amongst the four stages with respect to tree-ed areas should be proportional to the length of the different stages..

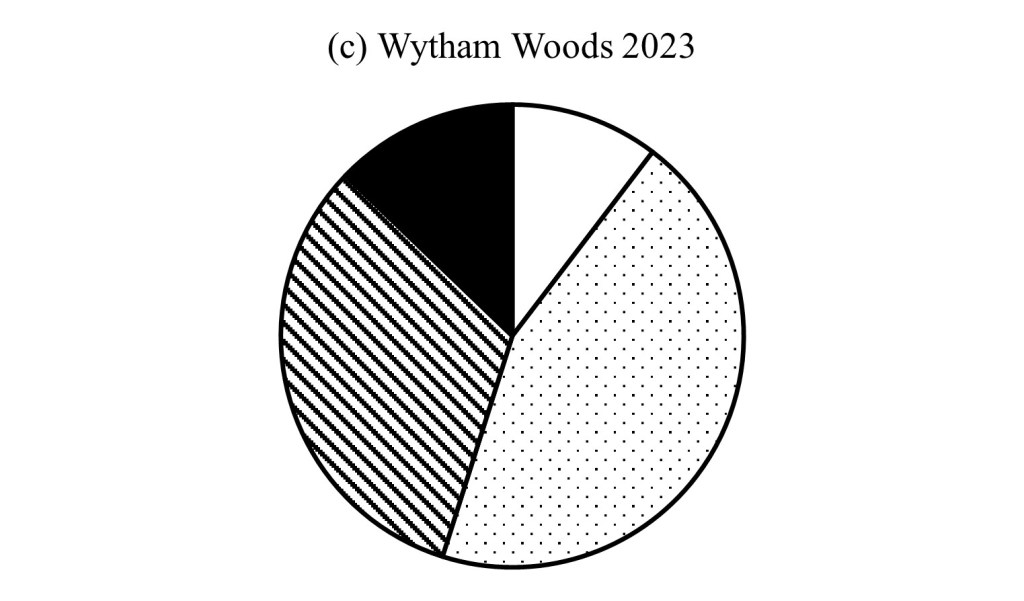

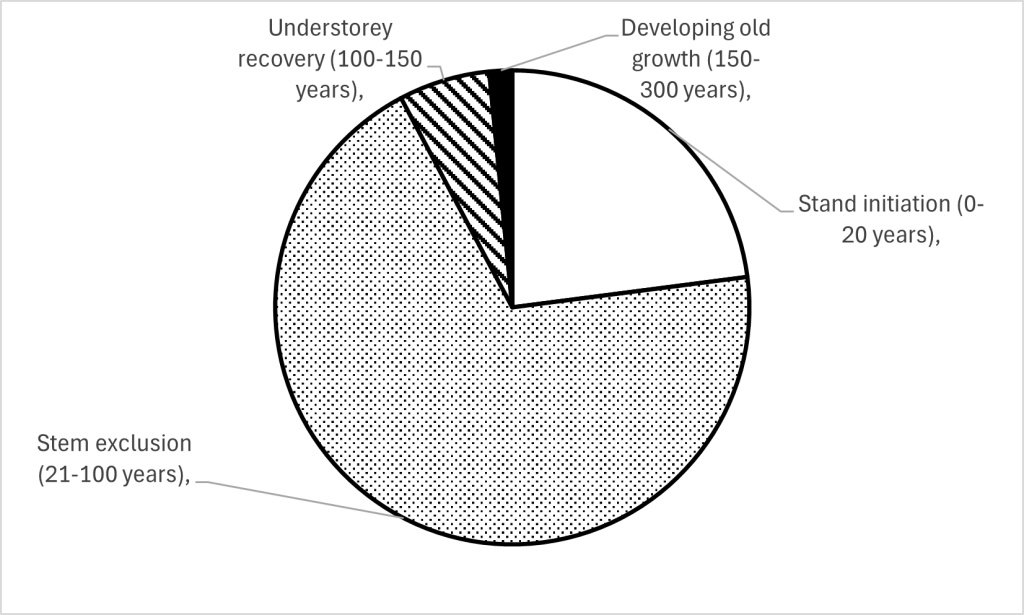

The proportion of a landscape at different stages assuming the indicated length of stages and 300 year life span for most trees, above, and the proportions of different stages in Wytham Woods (below) in 1974 and 2023.

This breakdown for Wytham Woods in 1974 and in 2023 was based on tree sizes in 10x 10 sample plots. Wytham was heavily biased in 1974 towards the younger growth stages, a consequence of wartime felling and subsequent restocking; fifty years on there is more variety, but the oldest stage is still underrepresented – it needs more time.

A fifth category can be added to the model: ‘open space’ or the non-tree-covered areas. These could be permanent, a fixed percentage which does not affect the proportion occupied by the different stages over the rest of the landscape. Alternatively the open space might be temporary, a regular part of the growth stage cycle, coming before stand initiation. In this case its length is added into the cycle (let’s say, 50yrs for the example below), which will then change the relative proportions of the other stages, and hence their extent in the landscape.

Nationally the broadleaved woodland is re also heavily biased towards the younger stages. This stems from a high proportion of long-established broadleaved woodland being managed as coppice historically, and then being cut over during the World War II; plus the new woodland created over the last 50 years by planting and natural colonisation. What is lacking are stands developing old growth because most broadleaves are harvested before 150 yrs old.

These ideas provides a useful framework for considering the structure and dynamics of large-scale tree-ed landscapes, which can be applied whether the basic unit of regeneration is large or small, and whatever the distribution of the different age classes. They also provide a guide to what sorts of wildlife will thrive in different landscapes. For example, coppice effectively kept much woodland in the stand initiation and stem exclusion phase; what we have seen since WWII is a shift largely to the stem exclusion phase and some understorey re-initiation. The species associated with the earlier stages are typically those that have been declining, but without much gain of species associated with developing old growth, because few stands have yet been left to grow on that long.

Of course these are just concepts, models, frameworks: real trees and woods (and their associated wildlife) don’t behave so neatly. There are other complicating factors, but starting with a simplification can be help in dealing with the complex.