Later today I will be joining a discussion about what is important about ancient woods and whether some characteristics are also shared with younger woodland. So, I am revisiting some of the history of the terms beforehand and how they have evolved.

Hayley – the quintessential ancient wood; and recent woodland in the Heart of England Forest

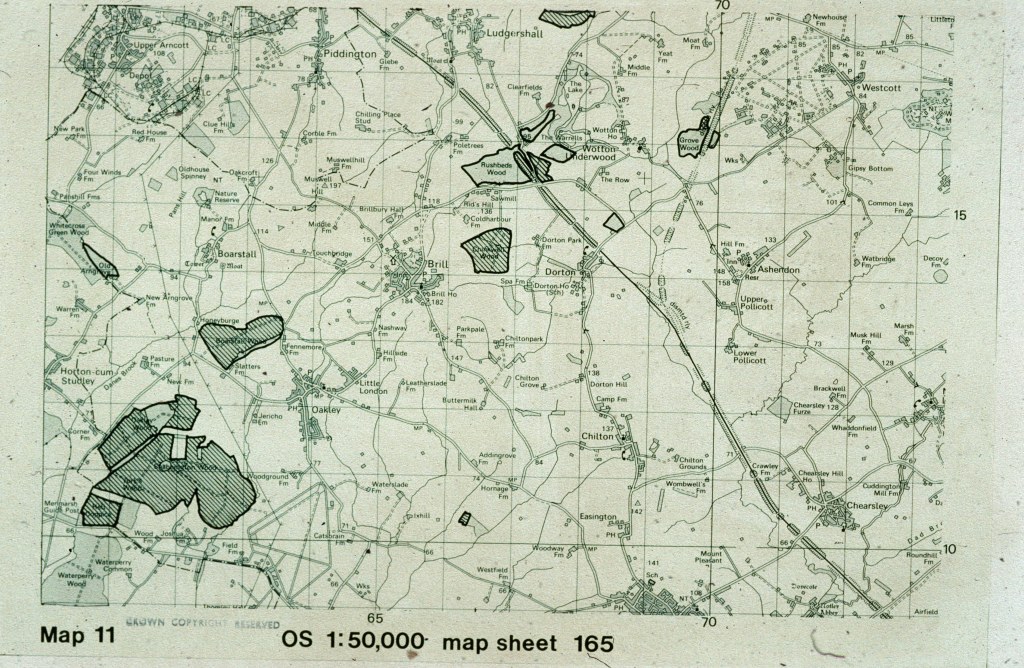

When the the Nature Conservancy Council’s Ancient Woodland Inventory project started in the early 1980s the aim was to try to identify all woods over 2 ha which appeared to have been continuously wooded since 1600 CE – the working definition used for ‘ancient woodland’. This would include all primary woods (if they still existed) and on the whole would include most of the richer woods for conservation. The methods were fairly crude: this was pre-GIS, there was little in the way of remote sensing, computer data-bases were fairly clumsy affairs (Goldberg et al., 2007, Spencer and Kirby, 1992).

Example of ancient woodland inventory map

One issue we faced was that, in practice there was often little direct evidence available for sites before c.1800 CE and indirect map evidence (shape, positing in parish, site name) was use to infer likely continuity for the period 1600-1800 CE and so the inventories were described as ‘provisional’. It was accepted that if further evidence (for or against continuity) emerged as a result of new conservation surveys or when a site was being considered for development or forest intensification, then the ancient label might be changed if necessary.

When the inventory moved into Scotland there were no early one-inch Ordnance Survey maps such as were used in England and Wales to get back to the woodland cover in the early 19th century. Instead inventorers had access to 18th Century maps prepared by William Roy, but only black and white copies. They could identify woodland if tree symbols were shown, but not the wider areas marked by green wash; these areas that might qualify as ancient, were likely to be missed. The first six-inch maps were much more accurate but being late 19th Century they included much relatively new afforestation that was by then more widespread in Scotland than in England. There was a risk that large areas that were not ancient might be included on the inventory if six-inch maps were used.

Part of the Black Isle (Ross and Cromarty) 1871-73. All the woodland shown is Long-established, but most is probably 19th century plantings.

So, a new category was introduced ‘Long-established’ for woods that were on the six-inch maps, but not apparent on Roy maps (Roberts et al., 1992). These were then split into those that appeared to be semi-natural (based on their shape, map symbols, place in landscape etc) – Long established, semi-natural origin; and those that appeared to be nineteenth century plantations – Long-established, plantation origin (LEPO).

The Long-Established category was thus introduced for pragmatic reasons, in recognition that some, but not all of these woods, really were ‘ancient’, but we just did not have the evidence. Subsequently a revision of the Ancient Woodland Inventory in Wales used the 19th Century six-inch maps to identify a Long-Established woods category alongside ‘Ancient’; and the revisions underway in England are as well.

This brings to the fore a second issue inherent in the ancient woodland inventory approach: the use of a simple definition date. Peterken (1977), (Peterken, 1983) set out why 1600 CE was chosen, but it created a ‘cliff-edge’ whereby a wood created in 1599 CE (ancient) is deemed a lot more valuable in wildlife terms than a wood that came into existence, two years later, in 1601 CE (recent). Some subsequent work has highlighted that fewer ancient woods than perhaps we thought in the 1980s are actually primary – many have had an open phase prior to 1600 CE (Day, 1993, Webb and Goodenough, 2018); moreover while solidly ancient in documentary terms, some woods show few classic ancient woodland features in the field. Other woods of clear 18th and 19th Century origin contain species or features that might suggest they were ancient (Barnes and Willliamson, 2015).

(a) Looks like and ancient woodland, but has periods of clearance pre-1600 CE; (b) maps suggest strongly this area is ancient but there are few ancient woodland features on the ground.

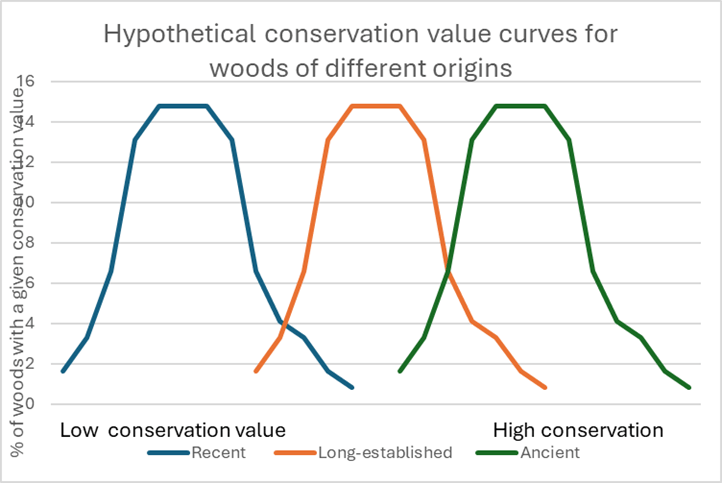

There definitely are links between woodland history and the presence of particular features or values but this is a general trend, not absolute in every case. There are overlaps in conservation values between the different historical categories (see figure below), but we do not know by how much, what the shapes of the curves are, how they differ for different ‘ancient woodland features’ or in different parts of the country. We might for example expect more overlap between the curves in well-wooded areas and in the uplands, than in lowland arable counties with only small isolated woods. We might expect more overlap for birds, than for vascular plants. This makes for difficulties where policy and practice is based around the presence or absence of a wood at a specific time. There could be some interesting discussions ahead.

BARNES, G. & WILLLIAMSON, T. 2015. Rethinking ancient woodland: the archaeology and and history of woods in Norfolk., Hatfield, Hertfordshire, University of Hertfordshire Press.

DAY, S. P. 1993. Woodland origin and ‘ancient woodland indicators’: a case-study from Sidlings Copse, Oxfordshire, UK. The Holocene, 3, 45-53.

GOLDBERG, E. A., KIRBY, K. J., HALL, J. E. & LATHAM, J. 2007. The ancient woodland concept as a practical conservation tool in Great Britain. Journal of Nature Conservation, 15, 109-119.

PETERKEN, G. F. 1977. Habitat conservation priorities in British and European woodlands. Biological Conservation, 11, 223-236.

PETERKEN, G. F. 1983. Woodland conservation in Britain. In: WARREN, A. & GOLDSMITH, F. B. (eds.) Conservation in perspective. Chichester: John Wiley & Sons.

ROBERTS, A. J., RUSSELL, C., WALKER, G. J. & KIRBY, K. J. 1992. Regional variation in the origin, extent and composition of Scottish woodland. Botanical Journal of Scotland, 46, 167-189.

SPENCER, J. W. & KIRBY, K. J. 1992. An inventory of ancient woodland for England and Wales Biological Conservation, 62, 77-93.

WEBB, J. C. & GOODENOUGH, A. E. 2018. Questioning the reliability of “ancient” woodland indicators: Resilience to interruptions and persistence following deforestation. Ecological Indicators, 84, 354-363.