In 1544 George Owen acquired part of the Abingdon Abbey’s holdings in Cumnor parish (Grayson and Jones, 1955). The valuation noted that as well as the woodland ‘there be growing about the situation of the said manor and 18 tenements there 600 oaks and elms of 80 and 100 years growth whereof 400 reserved for timber to repair the houses standing upon the said manor and tenements and 100 valued at 8d the tree. And the 100 residue valued at 4d. the tree which is the whole.’ These would not have been very big trees, probably maiden stems of about 40-50 cm diameter at most, since most were earmarked for building work.

There is thus a long history of valuing trees outside woods, but for much of the 20th century they were rather ignored. The Forestry Commission, because of the way it was set up, was focused on woods and forests, not scattered trees on farmland and in towns and villages. They were a similarly a low priority for much of the conservation sector because the main protection mechanism – as Sites of Special Scientific Interest – was not that suitable for individual trees or scattered groups of trees. For farmers and planners trees were often in the way of their work and many were consequently cleared during the period of high farming from 1950-1990 and ongoing urban development. Many elms were lost in the 1970s and 1980s to Dutch Elm Disease and those losses are now being repeated for ash with Ash Dieback.

An inconvenient tree garden tree being removed; an elm hedge, but no longer elm trees.

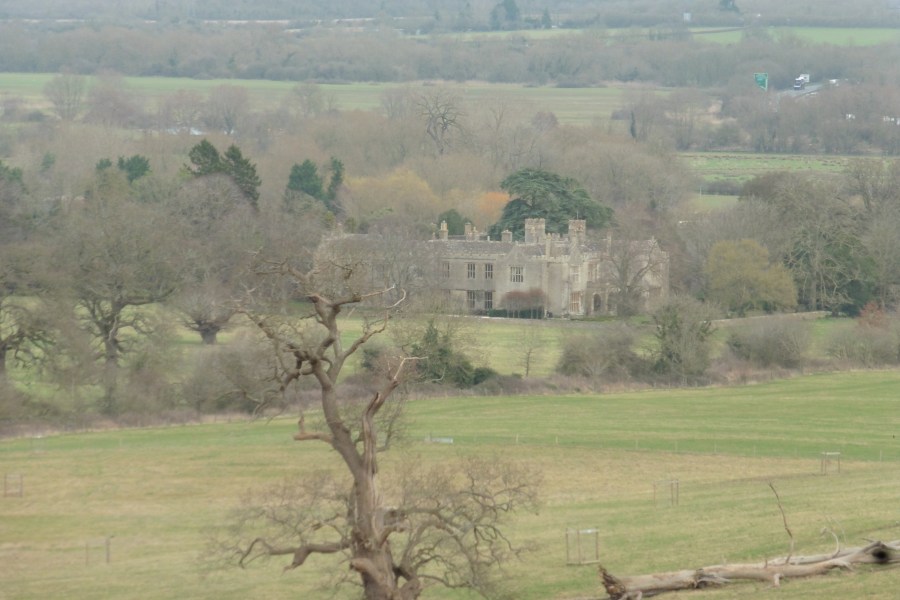

There were however few statistics on the number of trees outside woodland, where they were and what was happening to them. A difficulty is that trees outside woods are actually a lot of different things: garden trees, street trees, hedgerow trees, trees in ancient parks, trees in modern urban parks, orchards, modern agro-forestry alley trees, etc. Unlike in the 16th century they are not used much for house repairs or other building works, but they do have a wide range of other values, as stores of carbon, buffers against noise and pollution, provision of fruit and nuts and for their wildlife value. This last ranges from rather low (the leylandii hedge in the back garden of my house in Peterborough) to international (with some of the large ancient oaks in Britain).

Street trees, an old park tree, a modern park tree

Recent research is bringing their collective contribution to the tree cover of Britain into the spotlight. The Forestry Commission has extended the National Forest Inventory downwards from 0.25 ha, to cover small woods of over 0.1 hectare, smaller groups of trees and lone trees (Brewer et al., 2017). This shows that they occupy about 3% of the land surface, not insignificant when the cover of all woodland is only c,14% land surface. Remote sensing has been used to produce a first map of trees outside woodlandal although as might be expected this needs refining https://ncea.maps.arcgis.com/apps/instant/sidebar/index.html?appid=cf571f455b444e588aa94bbd22021cd3 .

A project funded by Defra has been looking at what can be done to encourage the renewal of this resource through encouraging the planting and protection of new trees outside woods https://treecouncil.org.uk/science-and-research/shared-outcomes-fund/. Meanwhile the outputs from the Ancient Tree Inventory are highlighting this particular subset of non-woodland trees with particularly high wildlife values (Nolan et al., 2020) and a project by the Tree Council and Forest Research has explored alternative ways in which special trees might be protected. (Allan et al., 2025).

New tree planting on the edge of a village; what is the best way to protect this ancient oak?

We now know we have 3% more land under trees than before, but we have not suddenly created 3% more tree-cover, or its equivalent of stored carbon, wildlife etc. Trees outside woods deserve the attention that they are getting and more resources and research; but we must avoid making this a zero-sum game where other aspects of tree and woodland work are reduced accordingly. Instead we should use the results to argue for more funding to be coming treewards.

ALLAN, J., BENHAM, C., TAYLOR, T., STOKES, J., BROCKETT, B. & AMBROSE-OJI, B. 2025. Protecting trees of high social,cultural and environmental value. The Tree Council/Forest Research.

BREWER, A., DITCHBURN, B., CROSS, D., WHITTON, E. & WARD, A. 2017. Tree Cover Outside Woodland in Great Britain. Forestry Commission: Edinburgh, UK.

GRAYSON, A. J. & JONES, E. W. 1955. Notes on the history of the Wytham Estate with special reference to the woodlands, Oxford, Imperial Forestry Institute.

NOLAN, V., READER, T., GILBERT, F. & ATKINSON, N. 2020. The Ancient Tree Inventory: a summary of the results of a 15 year citizen science project recording ancient, veteran and notable trees across the UK. Biodiversity and Conservation.https://doi.org/10.1007/s10531-020-02033-2