There are friends and colleagues who became ecologists because they were keen naturalists as children, spending a lot of their time birdwatching, collecting things, identifying plants; but I think imaginary forests shaped my liking for trees and woods as much as real ones did. I may not be the only one: at a recent conference in Birmingham one of the talks was from a PhD student working on the role and meaning of forests in fantasy literature.

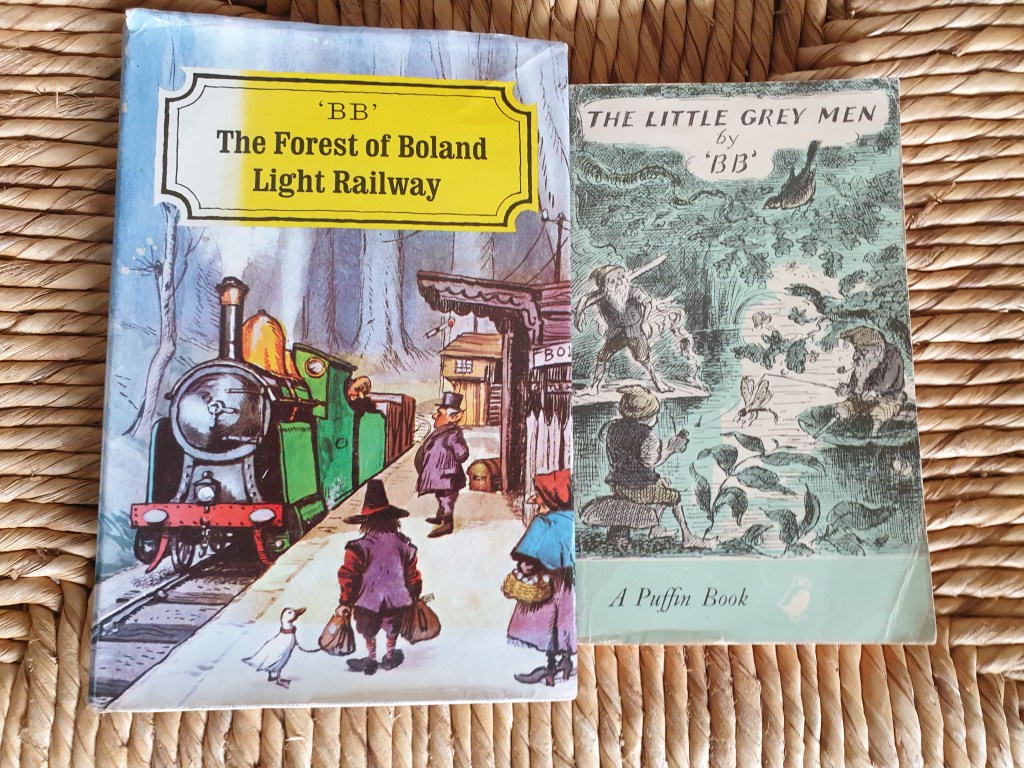

Certainly the first forests I drew were definitely not real. They were swathes of poster-paint green and brown that exasperated my primary school teacher; fortunately, none survive. Other early fantasy forests came in fairy tales and the stories of ‘BB’ – his Little Grey Men and the Forest of Bowland Light Railway. Real woods across the river had to wait until my brother deemed me old enough to join him in their exploration.

Books from a 1950s childhood

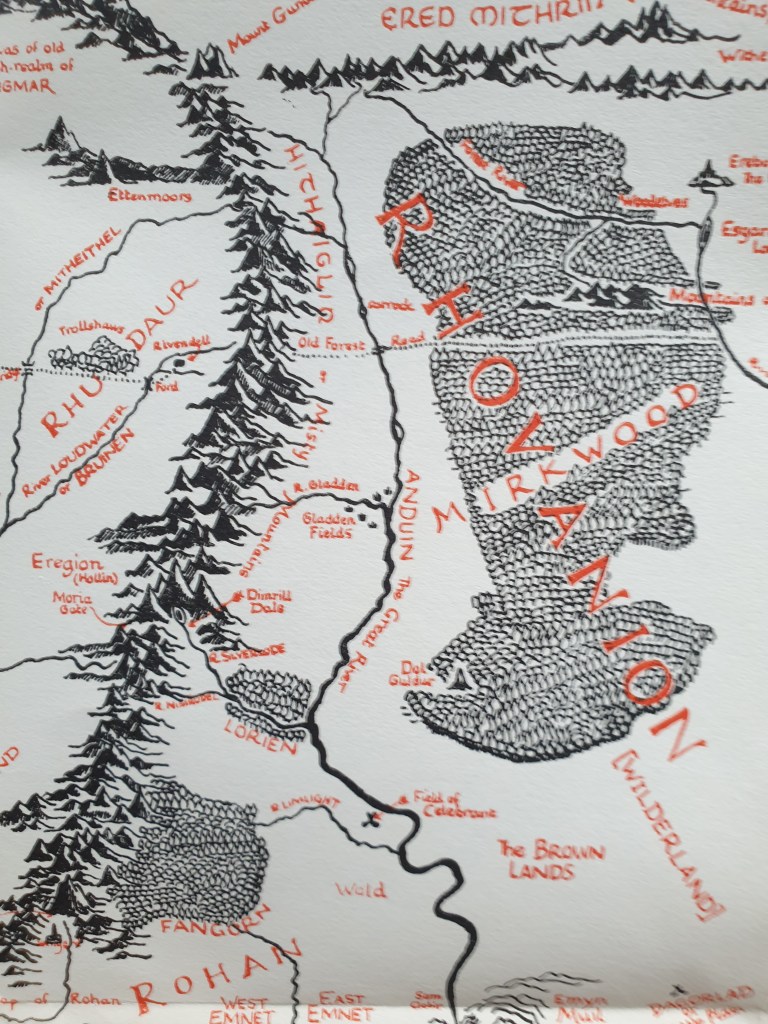

Later there would be the Forest Sauvage in T.H. White’s The Sword in the Stone (home of witches, wizards and the Questing Beast) and mighty Mirkwood (my brother introduced me to The Hobbit), with its giant spiders, butterflies in the tree-tops and occasional deer. Tolkein also conjured up, in Lord of the Rings, the Old Forest on the edge of Shire with its mercurial guardian Tom Bombadil and the vengeful Old Man Willow; Lothlorien a fading elven forest land ruled by Galadriel (shades of Rider Haggard’s She); and Fangorn, the aged Ent and his legions of Huorns – ents that had become very tree-like most of the time – moving to war on the orcs and axes of Saruman.

Tom Bombadil and River-woman’s daughter Goldberry; the three great forests of Middle Earth

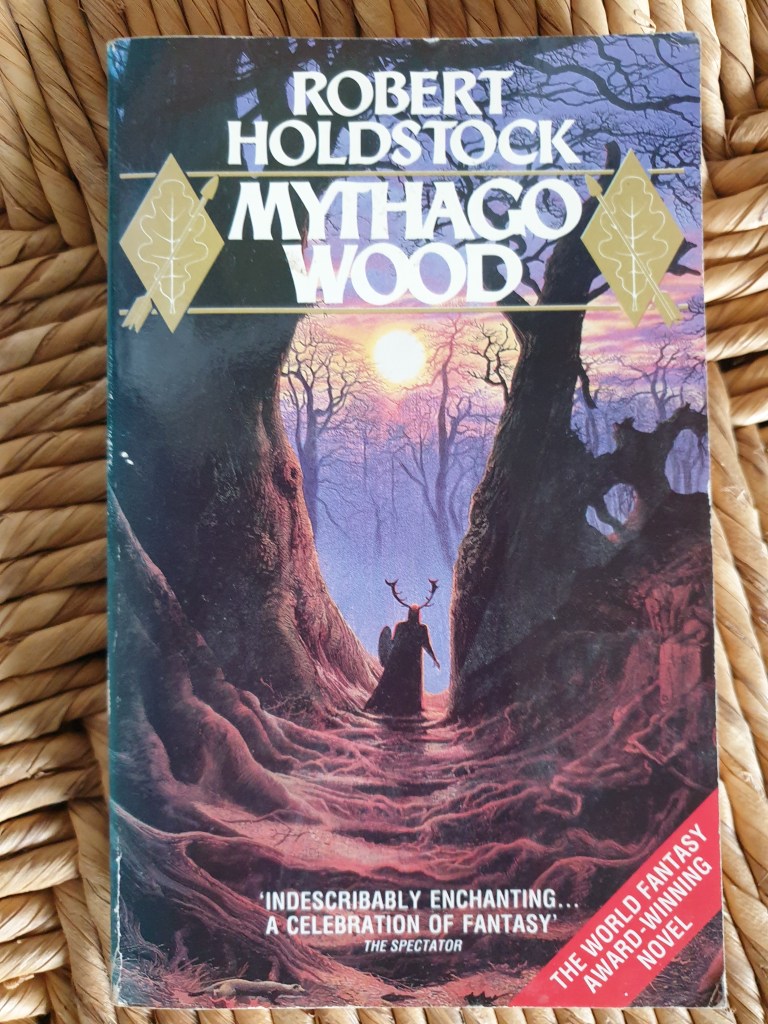

And what would I give to walk in Robert Holdstock’s Mythago Wood where the deeper you go, the further back in time you are, such that eventually there is the wildwood. Or to see the Diamond Tree groves that James H Schmitz describe in a short story, Balanced Ecology, where all the strange creatures, apparently distinct species, are interconnected and unite to manage the human colonists, allowing a sustainable harvest of the trees to avoid their over-exploitation.

Even when I am pretending to be a ‘serious scientist’ there is an element of woodland magic lurking in my imagination waiting to be let off the leash. Perhaps today, round that next corner I might, like Thomas the Rhymer, meet the Queen of Elfland in her mantle of grass-green silk.

However, even without such a meeting trees and woods are fantastic: how else to explain the existence of strange plants that appear in the same place but only for a few weeks each year; cockle shells, embedded in an ancient limestone ridge 150 m above current sea-levels.

There are burrs on oak trees, looking like an elephant; ancient trees that were starting to grow when the Wytham estate was divvied up between the cronies of Henry VIII, Sir John Williams and George Owen; and fine thread-like wefts of fungal mycelia, connecting and transporting materials between the roots of forest giants. Such creatures will have to do, until I find the way to Mirkwood.

The ‘elephant tree’ at Windsor; the 500-600 yr old Broad Oak at Wytham; toadstools tracing the line of a tree root or rotting branch.

Did Robin Hood really exist, almost certainly not; could he have hidden in Sherwood Forest, no, because it was open wood-pasture. But he is still important and matters, if some of the people who visit Sherwood because of the outlaw, go away more interested in the trees and woodland of real life.

The Major Oak at Sherwood, where Robin Hood did not hang out with Maid Marian.