Words are tricky; when I use a word, I know what I mean it to mean (usually), but you may interpret it differently. This may be because a term does not have a fixed definition – how many hours have I spent in meetings debating exactly what should count as rewilding, or what is and is not wood-pasture?

This is a wood-pasture, but what about this?

Meanings may also be clear within a discipline but convey something else to others. Foresters have for a couple of centuries used ‘natural regeneration’ to mean the process of getting trees established from seed dropped from the tree, as opposed to planting young trees grown elsewhere. To achieve this there may be interventions such as thinning to provide more light for the seedlings, ground disturbance and protection through fencing against herbivores. So, it is not always entirely ‘natural’ in the sense of not involving human action. Foresters have never hidden this aspect of the term ‘natural regeneration’ used in a forestry sense, but it seems to have come as a surprise to some ecologists recently.

Unassisted natural regeneration of ash (now mostly dead!); trial ground scarification to encourage oak regeneration in the Forest of Dean

Listeners may also interpret words (sometimes correctly, sometimes not) based on their background and past experiences. There is a tendency in parts of the conservation sector to think that if a professional forester refers to management they must mean going in and felling lots of trees, while in parts of the forestry sector there is a reluctance to recognise that even if production is not one of the objectives woods are not necessarily ‘unmanaged’. Woodland management, to me, means thinking about what you want a wood to provide and then working out the best ways to deliver that. It can mean everything from a deliberate decision to leave a wood completely alone, to using it as stock shelter, to harvesting the timber with big machinery.

A managed wood under minimum intervention; another managed wood being harvested.

Most of our woods, and many of our non-woodland treescapes, have had wood extracted from them in the past, from the ancient coppices and wood-pastures of the south-east to the Sitka spruce forests of the north-west. This has shaped their character, literally in terms of the shapes, ages and distribution of trees, to the wildlife that is currently found in them. That extraction was done because the wood was needed, was valuable as fuel, as raw material for pulp, for construction.

SSSI oak woodland, one with coppice history, the other managed as high forest.

Home-grown wood is likely to continue to be needed in future, particularly as we become more sensitive to the environmental footprint overseas of our dependence on imports (c80% of wood and wood-products used in the UK). This generates two challenges. The first is to decide what levels of extraction are compatible with maintaining the other values that we associate with the woods as they currently are. The second is planning the evolution and creation of the woodland for the future such that it can allow the levels of extraction (both quantity and quality) that as a society we think we will need.

The current discussions about whether more woodland should be ‘managed’ is partly about ensuring that thought is given to how our tree cover is going to cope with the increasing pressures from climate change, pollution, high deer numbers etc. It is though also about the potential for increasing what can sustainably be extracted in terms of wood and timber. We do not have to harvest wood from every patch of tree cover in the country, but we should try to increase the full range of goods and services that the present and future tree cover of the country can provide.

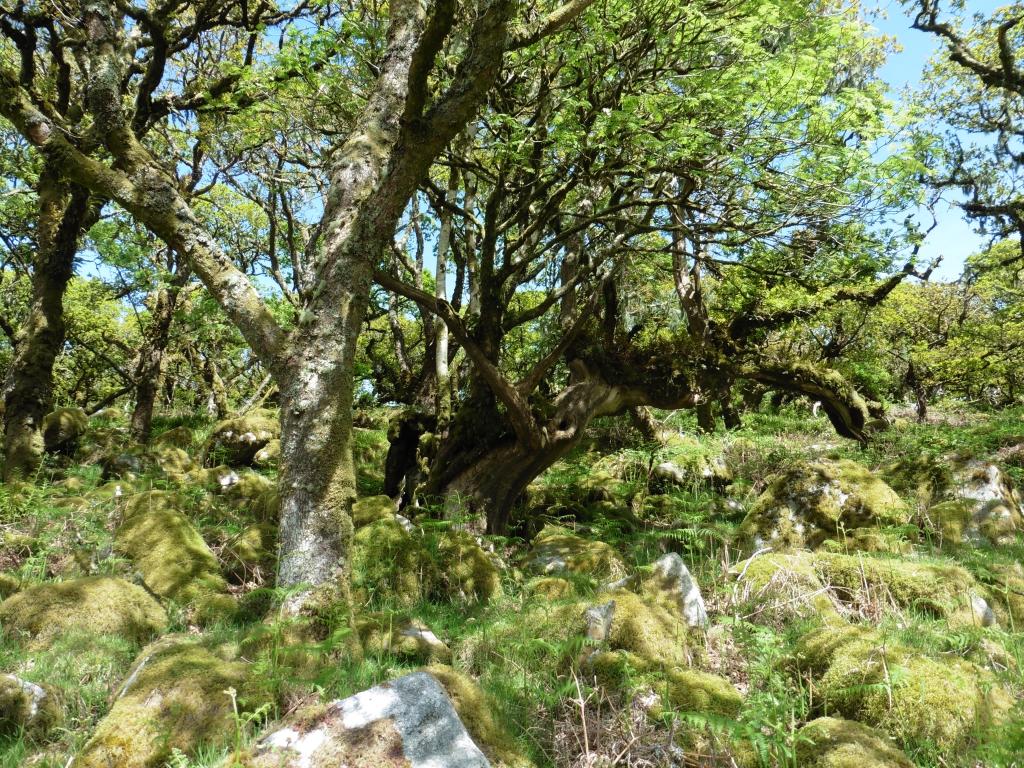

Harvesting would not be appropriate in Wistman’s Wood, but there might be scope in this stand in the Wye Valley?

It is, therefore, legitimate to ask the forester* who is responsible a woodland reserve to consider what (if any) level of wood output is compatible with their other interests on that reserve. After all we demand (through regulations, standards and grant conditions) that foresters managing woods primarily for timber extraction make some provision for biodiversity, soil and water protection.

*Anyone who is responsible for a woodland is acting as a forester, whether or not they accept that appellation, are trained as such, or are a member of the relevant professional institute; just as anyone who manages land for growing crops or livestock is effectively practising as a farmer.